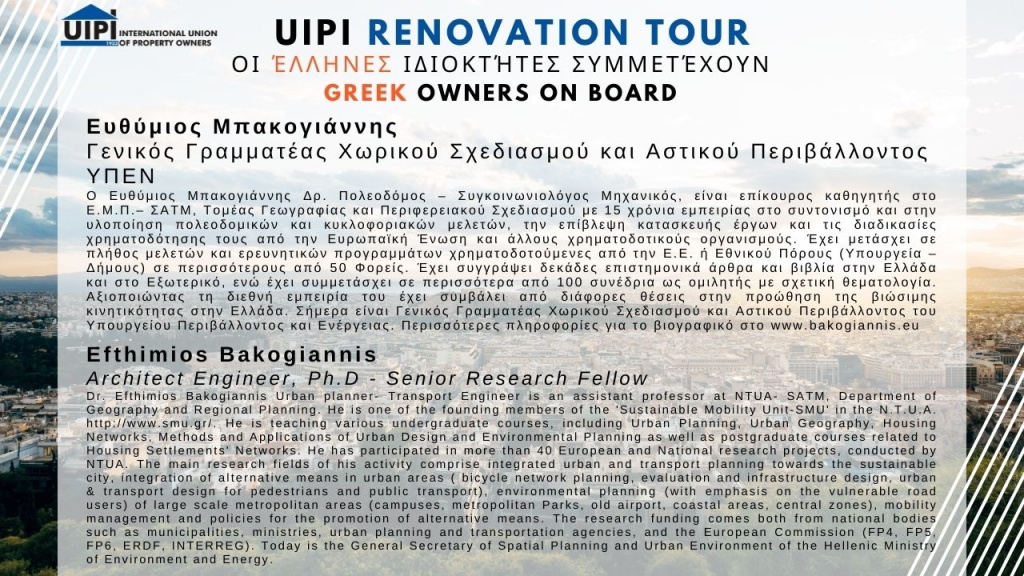

Portrait of Kadri Tüür and her Rehi in Muhu Island - Estonia

For the fourth portrait of UIPI Feature Series on Building Heritage, we head to the North of Europe and the Baltic Region. More precisely, we go to Koguva in the Baltic Sea, down to the Island of Muhu. With slightly less than 200 km2 and 2000 inhabitants, Muhu managed to preserve its original features. There, we meet Kadri Tüür, a young mother who decided to take over and renovate her family-owned ancient rehielamu (or rehi) into a modern dwelling. A Rehi is the traditional Estonian farmhouse which combines living space, a place for cooking and drying crops, and threshing barn. The house belongs to Kadri’s family since the eighteenth century, but there is written evidence of the existence of the settlement since 1532, so the farm might be even older. About 20 years ago Kadri took over the house, which previously belonged to a relative of hers. She then moved there permanently in 2002. Since then, Kadri has been taking special care of this little gem located in the beautiful Baltic landscape. Here are her story and the story of her property.

Credits: Lauri Kulpsoo

"It is important to try to give a voice to cultural heritage property owners and demonstrate that, behind each and every building, there are great stories and human adventures."

Kadri, tell us about your motivation to own and live in this house and to preserve it?

I like living in this house! I have never had any better living conditions neither in Estonia nor abroad. I also want to give my children the experience to live in a more traditional way, but at the same time in a well-suited house with modern living standards. These types of houses have been built for over 1000 years in Northern Latvia, Estonia and even North-western Russia, since they are suited to the local weather conditions.

Would you have an anecdote or memory to share with us that made you feel proud to be the owner of this property?

I remember one day, when I started settling in. I was hanging up the curtains, my cousin came for a visit with his girlfriend. After taking a look at my house, she ended up asking me: “Are you intending to stay here overnight?”, to which I replied “Yes, I actually intend to stay here for the rest of my life!”. At that moment she didn’t have anything more to say. It seems that for those people that have grown up in cities this is not more than a pile of woods. Well, it doesn’t look magnificent at first sight, but it is indeed very cosy! This house has great quality and you can actually live in it.

How do you keep the house in good shape and preserve its history and architectural character?

Houses are meant to be used for living, so the most reasonable thing to do with a cultural heritage house is to permanently live in it. Ours is a wooden house. It is made of logs, so in order to prevent them from rotting, it has to be constantly protected against water infiltration. Hence, it is important to have a good roof and to regularly heat the house and keep an eye on its inside and outside spaces. Historically, a typical Rehi had several functions: it was at the same time a house and a shelter for animals. Therefore, these houses are normally long, as they had to accommodate all these activities under the same roof. Ours is around fifty meters long. Traditionally, Rehi faces South to take advantage of the maximum amount of daylight for indoor activities. They also have roofs with long eaves that help to protect the walls from rain and snow in the winter and provide some shade during mid-summer. Therefore, during summertime, the house stays nice and cool, while during the winter it feels warm inside. This turns out to be quite convenient and it shows how well-conceived these buildings were!

Have you undertaken actions to adopt this building to modern standards and how did you manage to do so while preserving its heritage value?

Have you undertaken actions to adopt this building to modern standards and how did you manage to do so while preserving its heritage value?

When I took over the house, we only installed running water and a sewage system. Funnily, people sometimes question whether it is permitted to install running water in a listed building. My answer is simple: “It is allowed and there isn’t any problem as long as you do it properly!”. We also have Wi-Fi connection. I think these utilities cover most of the needs according to modern living standards.

In this type of houses, windows are pretty small. Some owners have tried to enlarge them, but this needs to be done very carefully to avoid structural problems by cutting too wide openings on the walls. As our house is under heritage protection – as all houses in this village – we are not allowed to make any changes on its facades nor alter its external appearance. So we had to refurbish it from the inside. We have not made any additional holes in the walls. My father who is a craftsman and I just used what was available and tried to make it as functional as possible. Originally, the largest room was used for drying grain, so it is relatively spacious and with high ceiling, compared to rural houses in many other parts of Europe. We use it as the main room of the house: we cook, live, work and relax in this room. This is the centre of the house and our communal space.

What are the current national or local policy framework and financial incentives in force? Do you make use of them? What could be improved?

What are the current national or local policy framework and financial incentives in force? Do you make use of them? What could be improved?

In Estonia, the National Heritage Board has a financing scheme for houses that are registered as heritage buildings. It provides financial support for restoration works. I am applying every year, but I haven’t been always successful. In my experience, they tend to support the renovation of neglected buildings at risk of collapsing instead of those that are inhabited and taken care of. For example, you can hardly get support to change the roof. I wanted to change mine but since it is hand-crafted, it is quite expensive, so I could not afford it on my own. My application is still pending but I will keep on sending it again and again. It is very good that this financing scheme exists, but the eligibility criteria might have to be reconsidered.

The Estonian Open-air Museum has also a section for Rehi houses, where they map and register all these types of houses and provide information to the owners on how to maintain and preserve them. Nowadays, most of the owners of these buildings have lost the intergenerational contact with the previous generations who had the knowledge of how these houses naturally used to function and how they can be maintained. Therefore, they need advice, and this is what the Centre of Rural Architecture does. What they are doing is also very important, as important as the financial support!

In your opinion, how can we motivate private owners of cultural heritage buildings to have an interest in maintaining their properties?

I think this kind of interviews helps. Good stories motivate best! So, I think it is important to try to give a voice to cultural heritage property owners and demonstrate that, behind each and every building, there are great stories and human adventures. Sharing these stories can help and motivate those who are facing the same kind of challenges, or who are thinking to buy an uninhabited old Rehi house. It shows them that living in a heritage house is not too difficult after all, in terms of maintenance and preservation. If you get to know other people’s stories you find out that cultural heritage buildings make a lot of sense and are very well structured! They also support and give strength to the local identity of a place. When I think of Europe as a whole and as a concept, it is a cultural mosaic with many unique local identities; valuing them is a European thing to do.

What would be your idea on how to share the heritage value of your property with the public?

The National Heritage Board compiles information about listed buildings and, on their website, we can see pictures of the houses and the evolution of their surroundings. It is a good way to tell and disseminate the story of a building.

There are also more direct ways to share this patrimony. In the centre of our village, there is also a Rehi house that has been converted into a museum. The rest of the Rehi houses in the area are under heritage protection, but they are privately owned and inhabited, so not open to the public. Some of their owners have converted them into Bed & Breakfast allowing their guests to experience how it feels to live in such a house. Personally, I do not offer accommodation services, partly because I have young children. However, my house is open to visitors and guests. I always welcome friends, acquaintances and colleagues who pass by. This is my way of sharing our heritage! Friends often come over and help. There is always some work to do in such a big house with a relatively big yard. Mutual help and collective work are an old rural Estonian custom. They were part of a traditional agricultural practice and are now part of our lifestyle. You gather your friends, you all work together and have fun, and you increase the value of the final result.

If you were to give one advice to the generation that will take over this building, what would it be?

Live in it! Learn by experience! Do not try to impose your standards to the house, they might be proven wrong in the long run. On the contrary, get used to the house and understand how it works!

UPCOMING ARTICLE

In October, for our 5th portrait, we will meet a Norwegian lady who dedicated most of her life to preserve the national heritage and who has renovated several heritage properties.